Right now, you're more than likely spending the vast majority of your time at home. Someday, however, we will all be able to leave the house once again and emerge, blinking, into society to work, travel, eat, play, and congregate in all of humanity's many bustling crowds.

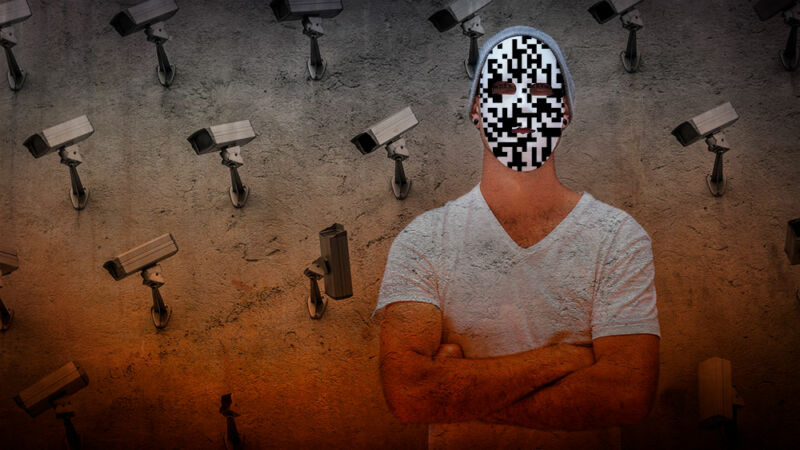

The world, when we eventually enter it again, is waiting for us with millions of digital eyes—cameras, everywhere, owned by governments and private entities alike. Pretty much every state out there has some entity collecting license plate data from millions of cars—parked or on the road—every day. Meanwhile all kinds of cameras—from police to airlines, retailers, and your neighbors' doorbells—are watching you every time you step outside, and unscrupulous parties are offering facial recognition services with any footage they get their hands on.

In short, it's not great out there if you're a person who cares about privacy, and it's likely to keep getting worse. In the long run, pressure on state and federal regulators to enact and enforce laws that can limit the collection and use of such data is likely to be the most efficient way to effect change. But in the shorter term, individuals have a conundrum before them: can you go out and exist in the world without being seen?

Systems are dumber than people

You, a person, have one of the best pattern-recognition systems in the entire world lodged firmly inside your head: the human brain.

People are certainly easy to fool in many ways—no argument there. But when it comes to recognizing something as basic as a car, stop sign, or fellow human being—literally the kinds of items that babies and toddlers learn to identify before they can say the words—fooling cameras is in many ways easier than fooling people. We're simply trained by broad experience to look at things differently than software is.

For example, if you're driving down the road and see a stop sign at night, you still know it's supposed to be "red." And if it has some weird stickers on it, to you it is still fundamentally a stop sign. It's just one that someone, for some reason, has defaced. A car, however, may instead "read" that sign as a speed limit sign, indicating it should go up to 45 miles per hour, with potentially disastrous results.

Similarly, a person looking at another person with a weird hairstyle and splotches of makeup on their face will see a human, sporting a weird hairstyle and with makeup on their face. But projects such as CV Dazzle have shown that, when applied in a certain way, makeup and hair styling can be used to make a person effectively invisible to facial recognition systems.

Heavy, patterned makeup and hair straight out of a JRPG are impractical for daily life, but all of us put on some kind of clothing to leave the house. As Ars' own Jonathan Gitlin has described, the idea of using the "ugly shirt" to render oneself invisible to cameras has been a part of science fiction for a decade or more. But today, there are indeed computer scientists and artists working to make invisibility as simple as a shirt or a scarf... in theory, at least.

Digital and physical invisibility

Two decades of Harry Potter in the public imagination have cemented for millions the idea that a cloak of invisibility itself should be lightweight and hard to perceive. The reality, on the other hand, is not exactly subtle—and still very much a work in progress.

"If you wanted to do like a Mission Impossible-style heist of the Smithsonian, I don't think you'd want to rely on this cloak to not be detected by a security system," computer science professor Tom Goldstein, of the University of Maryland, told Ars in an interview.

Goldstein and a team of students late last year published a paper studying "adversarial attacks on state-of-the-art object detection frameworks." In short, they looked at how some of the algorithms that allow for the detection of people in images work, then subverted them basically by tricking the code into thinking it was looking at something else.

It turns out, confounding software into not realizing what it's looking at is a matter of fooling several different smaller systems at once.

Think about a person, for example. Now think of a person who looks nothing like that. And now do it again. Humanity, after all, contains multitudes, and a person can have many different appearances. A machine learning system needs to understand the diverse array of different inputs that, put together, mean "person." A nose by itself won't do it; an eye alone will not suffice; anything could have a mouth. But put dozens or hundreds of those priors together, and you've got enough for an object detector.

Code does not "think" in terms of facial features, the way a human does, but it does look for and classify features in its own way. To foil it, the "cloaks" need to interfere with most or all of those priors. Simply obscuring some of them is not enough. Facial recognition systems used in China, for example, have been trained to identify people who are wearing medical masks while trying to prevent the spread of COVID-19 or other illnesses.And of course, to make the task even more challenging, different object detection frameworks all use different mechanisms to detect people, Goldstein explained. "We have different cloaks that are designed for different kinds of detectors, and they transfer across detectors, and so a cloak designed for one detector might also work on another detector," he said.

But even when you get it to work across a number of different systems, making it work consistently is another layer.

"One of the things we did in our research was to quantify how often these things work and the variability of the scenarios in which they work," he said. "Before, they got it to work once, and if the lighting conditions were different, for example, maybe it doesn't work anymore, right?"

People move. We breathe, we turn around, we pass through light and shadow with different backgrounds, patterns, and colors around us. Making something that works when you're standing in a plain white room, lit for a photo session, is different from making something that works when you're shopping in a big-box store or walking down the street. Goldstein explained:

Modifying an image is different than modifying a thing, right? If you give me an image, I can say: we'll make this pixel intensity over here different, make that pixel intensity over there a little more red, right? Because I have access to the pixels, I can change the individual bits that encode that image file.

But when I make a cloak, I don't have that ability. I'm going to make a physical object and then a detector is going to input the image of me and pass the result to a computer. So when you have to make an adversarial attack in the physical world, it has to survive the detection process. And that makes it much more difficult to craft reliable attacks.

All of the digital simulations run on the cloak worked with 100-percent effectiveness, he added. But in the real world, "the reliability degrades." The tech has room for improvement.

"How good can they get? Right now I think we're still at the prototype stage," he told Ars. "You can produce these things that, when you wear them in some situations, they work. It's just not reliable enough that I would tell people, you know, you can put this on and reliably evade surveillance."

Signal to noise

Becoming invisible to cameras is difficult, and for now at least, you're going to look really funny to other humans if you try it. An absence of data, though, isn't the only way to foil a system. Instead, what if you make a point of being seen, and in doing so generate enough noise in a system that a single signal becomes harder to find?

That's the approach designer Kate Bertash takes with her Adversarial Fashion product line, which she presented at DEFCON in 2019. Her prints are designed first and foremost to mess with automatic license plate readers (ALPR), systems that scoop up images from the fronts and backs of everyone's cars all over the country and hoover them into massive databases.

The privacy implications behind the mass collection of license plate data, in a country where more than 80 percent of us have to drive a car most days, are staggering. In Virginia, courts have ruled that holding onto the data violates privacy law. In California, Bertash's home state, a recent audit found that data collected from these ALPR systems is poorly regulated, poorly handled, and ripe for abuse.

The shirts, dresses, outerwear, and accessories Bertash sells are designed to trigger those readers and fill them up with junk data. And because human people can and do see your clothes when you wear them, the fake plates spell out the Fourth Amendment—the one that protects Americans from "unreasonable search and seizure."

Much like Goldstein, one of the major challenges Bertash encountered creating her design was figuring out how to apply it across different systems. To that end, she used two different commercial applications—one open source, and one closed—to create the design.

Using both was instrumental, Bertash explained, "because I have to be able to design experiments where I'm still going to get meaningful information back, even if I cannot see the complete source and see what it's looking at, what's important to the image to have it be detected or not."

Some of those features turned out to be somewhat unexpected, she added: things that give the impression of screws, where a real license plate would be attached to a car, or some kind of "garbage" on the image in the place where registration stickers or state slogans would tend to go.

The mainstream: Where art and science meet

Goldstein is not the only researcher working on the problem from a computer science angle, and Bertash is not the only designer tackling it from the art side. As use of surveillance systems grows and becomes endemic globally, designers worldwide are rising to meet the challenge in a variety of ways. Some, like sunglasses or infrared-blocking scarves, may be able to go mainstream quickly if mass-produced. Others, including Goldstein's "cloaks" or similar shirts made by a team of researchers from Northeastern University, IBM, and MIT, are a whole lot less likely to catch on.

The trick to expansion is threefold. First, people have to be interested in wearing adversarial designs. Second, the design actually has to work as intended. And third: the design has to be something you wouldn't mind being seen wearing while also, ideally, being good-looking enough that others will want to wear it, too.

As both Goldstein and Bertash described it, one of the hardest parts of adversarial design is learning to understand the adversary. When you can't see under the hood of a system, it's harder to figure out how to foil it. Making something work is both an art and a science, and cracking the code requires a healthy degree of trial and error to figure out.

"It's an open area of research, what these [systems] are actually looking at, or what is important to the computer," Bertash said. But from where she sits, the key to going mainstream with adversarial fashion may be nothing more and nothing less than simply encouraging people to try.

"What is it that I should try first when I encounter a new system? That is a core skill that I think all of us can build out, especially people who are artists and designers or computer scientists," Bertash suggested. While it does take detailed science to try to reverse-engineer a complicated system, it's simpler than you might think to simply test if you, yourself, are able to foil one. All you need to do is unlock your own phone, activate the front camera, and see which ordinary, everyday apps—your camera or social media—can correctly draw the bounding box around your face.

Making yourself invisible to Facebook or Snapchat by itself won't make you invisible to all systems, of course. As Goldstein's research has shown, there are many, and they all work in different ways. But by diving into trial and error at home, anyone can begin to tease out some of the underlying principles black-box algorithms might be using on them.

"We have this notion that people who are going to help us get through the surveillance age are people who have special skills, like computer scientists," Bertash said. "I actually think the thing that we can do most to unlock the mainstream is to create tools that allow people who are not in these specialty jobs to be able to test things in their own closet.

"I have a full belief that we actually probably all own things that may exhibit some of the principles that we want to see in blocking image detection, or gait detection, or even facial detection," she continued. "And if you give people the ability to test it by themselves at home, and to do a sort of trial and error on their own, it can make them realize that they're smart enough to figure their stuff out. So we don't have to rely forever on experts to be the people that save us from surveillance."

"some" - Google News

April 10, 2020 at 06:45PM

https://ift.tt/2XrOBi2

Some shirts hide you from cameras—but will anyone wear them? - Ars Technica

"some" - Google News

https://ift.tt/37fuoxP

Shoes Man Tutorial

Pos News Update

Meme Update

Korean Entertainment News

Japan News Update

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Some shirts hide you from cameras—but will anyone wear them? - Ars Technica"

Post a Comment