Every oral argument sitting of October Term 2019 has had one potential blockbuster case, whether involving gay and transgender rights in October, DACA recipients in November, the Second Amendment in December, and religious rights in January, with the forthcoming March and April sittings having their own candidates. For the two-week February sitting, which has trickled into the first week of March, most people would pick Wednesday’s abortion case, June Medical Services LLC v. Russo, as the blockbuster.

But today’s case about the status of executive power and independent federal agencies, Seila Law LLC v. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, is a close second. There is a full courtroom this morning that includes political figures, the court’s extended family, high school students and others. They will soon hear a mostly riveting extended, 70-minute argument.

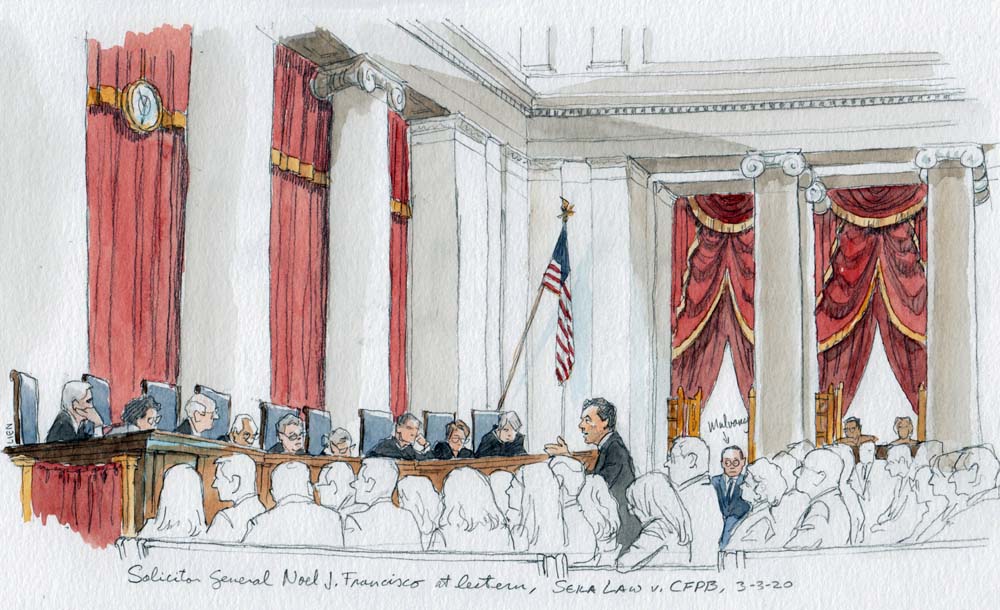

Solicitor General Noel J. Francisco at lectern during oral argument in Seila Law v. CFPB (Art Lien)

In the VIP section to the right of the bench, Maureen Scalia, the widow of the late Justice Antonin Scalia, arrives with her son John, a lawyer in private practice. Marcia Coyle reported in The National Law Journal earlier this week that Mrs. Scalia would be making her first visit to the courtroom for an argument since her husband’s death in 2016, apparently because three former Scalia clerks will be among the four lawyers arguing the Seila Law case this morning. (I’ll get to them momentarily.)

Also in the VIP box is Leonard Leo of the Federalist Society, a close friend of the Scalias and a key figure in recent court nominations. And taking the first seat closest to the justices is Mick Mulvaney, President Donald Trump’s acting White House chief of staff who is also still the director of the Office of Management and Budget. From late 2017 to late 2018, Mulvaney was the acting director of the CFPB.

Several people in the bar section walk over and greet the Scalias and Mulvaney before court begins. We don’t know whether Kathy Kraninger, the current director of the CFPB, is here today.

We’re also not sure whether any members of Congress are here today for the Seila Law argument, which involves whether the 2010 law that created the CFPB violates the separation of powers because the statute limits the president’s ability to remove the agency’s director.

To be sure, quite a few members of Congress have chimed in, with amicus briefs from three Republican U.S. senators (on the petitioners’ side), the House of Representatives (supporting the current structure of the CFPB) and 24 current or former Democratic members of Congress, also in support of the law.

Among the signers of the latter brief are former Senator Christopher Dodd, a Connecticut Democrat, and former Rep. Barney Frank, a Massachusetts Democrat, who co-authored the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, which created the CFPB.

Dodd is in the courtroom today, seated in the first row of the public gallery. After leaving the Senate, he led the Motion Picture Association of America before departing that job in 2018 and joining Arnold & Porter law firm.

Two other notable signatories of the “current or former members of Congress brief” are not here either, Sen. Bernie Sanders, Democrat of Vermont, and Sen. Elizabeth Warren, Democrat of Massachusetts. Both are evidently occupied with Super Tuesday events as they pursue their own chance to hold the job in which they would get to name a future CFPB director. Warren is credited with proposing the idea of something similar to the CFPB as a Harvard law professor in 2007.

When Chief Justice John Roberts was wrapping up his presidential impeachment trial duties in the Senate last month, he made a point to invite senators to visit the court.

“By long tradition and in memory of the 135 years we sat in this building, we keep the front row of the gallery in our courtroom open for members of Congress who might want to drop by to see an argument, or escape one,” Roberts said on February 5.

Since the court returned from its winter recess last week, no member of Congress has accepted the chief justice’s invitation. Or, if they have, the marshal’s office has not seated them in the middle front row bench referred to by Roberts. That bench sits empty during most arguments at the court, though there was an amusing moment a couple of years ago when a tourist tried to sit there.

A marshal’s aide was leading a group of 10 or 12 spectators to some of the wooden seats in the back alcoves of the court. To reach those seats, one has to move up the aisle of the public section and then cross over to the alcoves. As an aide was leading this particular group, someone in the middle of the pack spotted the empty center bench and thought that would be a good place to sit for the argument. Once the marshal’s aides noticed him, they gently reunited the errant spectator with the rest of his group.

When the courtroom takes the bench this morning, there is an opinion from Justice Samuel Alito in Kansas v. Garcia, reversing rulings of the Kansas Supreme Court that a provision of federal immigration law preempts state statutes used to prosecute identity fraud.

For the argument in Seila Law, Kannon Shanmugam is the first of three former Scalia clerks to step to the lectern. Amy Howe has this blog’s main account of the argument, which for most of the time was an engrossing seminar on the separation of powers but occasionally devolved into testiness.

Shanmugam, like the Trump administration, believes the structure of the CFPB is unconstitutional. But as a remedy, the Scalia clerk from October Term 1999 asks only that the CFPB’s civil investigative demand of his client, a California-based law firm and debt-relief concern, be invalidated.

As soon as his two minutes of uninterrupted argument are over, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg pounces with a question about whether the case presents a live controversy.

“Mr. Shanmugam, this case has kind of an academic quality to it,” she says. “You would be

harmed in the very same way if the president had the full removal power.”

Later, Ginsburg says the law puts only a “modest” restraint on the president’s power to remove the CFPB director, which is for “inefficiency, neglect of duty, or malfeasance in office.”

“It stops the president from at whim removing someone, replacing someone with someone who is loyal to the president rather than to the consumers that the Bureau is set up to serve,” she says.

Shanmugam responds that “what Congress was trying to do was to create an agency that precisely, because of its desire to protect consumers, was insulated from political control to the fullest extent possible.”

He illustrates that point with a rather vivid quote from a then-law professor. “As Elizabeth Warren, who was really the progenitor of the CFPB, said at the time, if Congress did not create an agency with functional independence, ‘my second choice is no agency at all and plenty of blood and teeth left on the floor.’”

That is not what Shanmugam wants, of course. “[W]e think the Constitution requires … that the president be able to remove a subordinate not just because of policy disagreements but because the president has lost faith in the official’s judgment or because the president wants someone of his or her own choosing.”

U.S. Solicitor General Noel Francisco, a Scalia clerk in O.T. 1997, moves to the lectern and has barely had a chance to assert why the president should generally have unrestricted authority to remove “principal officers” when Ginsburg presses him about the Department of Justice’s decision not to defend the structure of the CFPB.

“[M]ay I ask, isn’t it uncommon for the Department of Justice not to defend a statute passed by Congress?” Ginsburg asks. “How often has the SG declined to defend legislation adopted by Congress?”

The two go back and forth a bit before Alito swoops in to aid Francisco.

“General, isn’t it true that the Department of Justice has refused to defend the constitutionality of other federal statutes even when the President’s removal power is not at issue? … For example, the Defense of Marriage Act?” Alito says, in reference to a statute that President Barack Obama’s administration declined to defend in United States v. Windsor in 2013.

There is discussion of the political plum nature of early U.S. postmaster positions, as well as mentions of the Federal Reserve Board, the Federal Communications Commission and the Social Security Administration.

Justice Elena Kagan tells Francisco that a president’s removal of an executive officer “is like a nuclear bomb,” meaning a not easily accomplished objective when multiple other factors influence the amount of control the president might have, such as the appointment or the length of the officer’s term.

“The removal power is the principal power that the president uses not only to supervise the Executive Branch but to ultimately be held accountable to the people, which is, after all, the whole point,” Francisco says.

Paul Clement, a Scalia clerk in O.T. 1993, was recognized for his 100th Supreme Court argument last week. Serving as a court-appointed amicus to defend the structure of the CFPB, he begins his 101st argument with a sardonic observation that the two parties (Seila Law and the government) “are in violent agreement that the provision is unconstitutional.”

“There is a phrase that aptly describes what the Solicitor General wants from this court, and it’s an advisory opinion,” Clement adds. “And this court lacks jurisdiction to issue it.”

Justice Neil Gorsuch is the one to pounce on Clement when his uninterrupted time ends. He presses Clement on whether he is primarily asking the court to “DIG” the case, or dismiss it as improvidently granted.

“No, Mr. Justice Gorsuch, I think you should write a fine opinion that vindicates much of the reasoning of the dissenters in Windsor but reconciles it with the majority, and it’s not a DIG,” Clement says.

Even by the time Clement became a law clerk in 1993, the court had dropped its use of “Mr.,” as in “Mr. Justice Harlan” or “Mr. Justice Stewart,” and so forth. The change officially came when Justice Sandra Day O’Connor joined the court in 1981, though some older members of the Supreme Court bar could not shake old habits for quite some time after that. Clement may just be a bit of an “old soul,” as someone mentions in the press room later.

Clement’s tangle with Gorsuch is just beginning. Gorsuch says Clement’s answer “sounds like a DIG, but okay, fine.” The justice moves on to a merits question about whether Clement’s position might have implications for the removal of Cabinet members.

When Clement doesn’t, in Gorsuch’s view, provide a substantive answer quickly enough, the justice’s impatient side comes out.

“That’s not my question, Mr. Clement,” Gorsuch says. “If you could answer my question, I’d be grateful.”

Clement answers a further question with, “I offer you two limiting principles, which I think is two more than the Solicitor General offered you.”

Gorsuch, now even more grouchy, interrupts him to say, “If we could avoid disparaging our colleagues and just answer my question, I would be grateful.”

Clement answers and says he did not mean to disparage anyone.

The exchange is testy, perhaps not even the testiest one of the week. Yesterday, during argument in Department of Homeland Security v. Thuraissigiam, an immigration case, Roberts and Justice Sonia Sotomayor tangled over her questioning of Deputy Solicitor General Edwin Kneedler during his rebuttal time. After Sotomayor had gone on for several minutes in a long buildup to a question, the chief justice interrupted her to say, “I’m sorry, could you answer that, Mr. Kneedler?” But Sotomayor kept asking her question, which she eventually let Kneedler attempt to answer.

Maybe the justices need a break from each other, but they just had the holiday recess and the winter recess, each about four weeks.

The Seila Law argument continues with an unexpected reference to the coronavirus crisis.

“[N]ot every statutory responsibility needs to be conducted by the president himself,” Clement says. “In the current situation, you see people are trying to make a political football out of dealing with a pandemic disease. So maybe Congress decides: You know what makes sense, let’s have the head of CDC [the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] be protected by for-cause removal because that’ll make sure people get good advice and it doesn’t become political. That is the kind of sensible decision that Congress has been making for over 100 years.”

The argument continues with a low-key 10 minutes from Douglas Letter, representing the House of Representatives and defending the CFPB structure. And then two minutes of rebuttal from Shanmugam.

Finally, the chief justice is again recognizing Clement at the end of the argument. This time he delivers a scripted thank you that the court provides whenever a court-appointed amicus argues.

“Mr. Clement, this court appointed you to brief and argue this case as an amicus curiae in support of the judgment below,” Roberts says. “You have ably discharged that responsibility, for which we are grateful.”

In the press section, one regular quips in a loud whisper, “Justice Gorsuch dissents.”

Recommended Citation: Mark Walsh, A “view” from the courtroom: “Violent agreement” and some disagreement, SCOTUSblog (Mar. 3, 2020, 4:59 PM), https://ift.tt/38muPpU

"some" - Google News

March 04, 2020 at 04:59AM

https://ift.tt/38muPpU

A “view” from the courtroom: “Violent agreement” and some disagreement - SCOTUSblog

"some" - Google News

https://ift.tt/37fuoxP

Shoes Man Tutorial

Pos News Update

Meme Update

Korean Entertainment News

Japan News Update

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "A “view” from the courtroom: “Violent agreement” and some disagreement - SCOTUSblog"

Post a Comment